Shakespeare wrote ten plays called “The Histories,”

all focused on the British monarchy from King John to Henry the Eighth. Although he also wrote historical plays set

in Greece and Rome, only the British are marked “The Histories.” Even Macbeth,

that Scottish play, although set on the British isle and anticipating the reign

of King James the First, is listed under “The Tragedies.”

Exploring

the genealogies of the British monarchs is a fascinating way to navigate

Shakespeare’s history plays. A

genealogy, also called “a family tree,” is a charting of lineage. The absolute basis of the conflicts and

triumphs that define the course of Shakespeare’s history plays is how family

members fought and murdered each other to assume the throne. By the rule called “primogeniture”—the sequence

of descent was through the first-born son, and thereafter through his

progeny. If there were no children, the

throne would go to the next-born son—and so on.

But as with all things human, interpretations varied and, as we noted in

the post on “Come, here’s the map,” lesser family members were optimistic that,

given some finagling— murder and war—they could circumvent what was considered “the

natural course of things.”

Genealogies,

like all human constructions, are interpretations—selective attention. The above chart is focused on the figures

featured after Edward III (1327-1377).

King John (1167-1216) five generations back. This genealogy deletes Edward III’s two other

sons, as it does Henry IV’s other three.

What

we also don’t see is the intermarrying within Edward III’s descendants—an attempt

to secure claims to the throne. For

example, when Shakespeare presents Richard III as a disgusting lecher wooing

Ann Neville—whose husband and father-in-law his side of the family just

killed. But if we look at the genealogy

for Richard’s mother, we can see that Richard and Ann were cousins. Richard III is at the bottom right of the

tree; Ann was descended from Richard’s uncle Neville at the top left of the

chart:

In fact, Richard and Ann were cousins who had played

together and loved each other from childhood.

Ann had been married off by her “Kingmaker” father to—look at the first

chart above—Henry VI’s son, Edward, in the hopes of her becoming queen some

day. The marriage with Richard was

likely a marriage not only of power, but affection.

Go

back to the top chart: Another interesting piece of history is how Henry VII—Henry

VIII’s father—assumed the throne. Henry

V was married to Katherine Valois—in order to secure powerlines with France. Henry V was in Edward III’s direct bloodline.

When Henry died, his son, Henry VI, a nine-year old child, was crowned

king. His uncle Richard (descended from Edmund

of York, was made Regent—in charge of managing affairs of the state until Henry

VI came to maturity. The three Henry the VI plays focus on how this led to the

York’s wresting the throne from the Lancasters, descendants of John of Gaunt,

who had first dibs—being of an older son—on the throne.

Henry

the VII’s mother, Katherine of Valois, married Owen Tudor after Henry V

died. So, Henry the VII was not a blood

relation to Edward III. He was only

Henry V’s posthumous stepson. John of

Gaunt had four illegitimate children by Katherine Swynford, his long-time

mistress, whom he married after his legitimate wife, Blanche of Lancaster

died. These children were given the name

“Beaufort,” after a French lands John once owned. By rights, according to the customs of the

day, illegitimate children had no right to the throne. John had them legitimized after he married Swynford. But King Henry IV decreed they had no right

to the throne. So, it’s dicey. Margaret Beaufort, a female descendant of a

questionably legitimate progeny of John of Gaunt, was Henry VII’s mother. A very thin thread.

Go back to the top chart. You’ll see that Richard the III is descended

from Edmund of York. Richard’s oldest brother

became King Edward IV. Edward the IV

married Elizabeth, with whom he had Edward V and Richard. When Edward died, it was discovered that he

was still married to a previous betrothed. So, Elizabeth was not a legitimate

wife. So, after the middle brother,

George, was executed for treason (he had sided with the Lancasters and Henry VI

against Edward), Richard III had a right to the throne.

Shakespeare’s

The Tragedy of King Richard the Third, based on the works of Thomas More. More served John Morton, the Archbishop of

Canterbury, a political revile to Richard the III, so his history is biased, at

best. In his play, Shakespeare characterizes Richard as precipitating the

deaths of his nephews. But their legitimacy

had been countermanded, so he would not have had any reason for their demise.

Meanwhile,

mother Margaret was pushing for her son to wage war on Richard for the

throne. He prevailed at the Battle of

Bosworth. But wait. This is only a stepson in the lineage, and a son

of Margaret, who was not actually legitimate. To further secure his place on

the throne, Henry VII, he would have to go back and deny that Elizabeth Woodville

was a legitimate wife to Edward IV, so he could marry their daughter, Elizabeth

of York, as a royal.

Yes but—that means that little Edward V and Richard of

Shrewsbury had first dibs on the throne.

As Josephine Tey cogently argues in The Daughter of Time,

Margaret Beaufort and or he son Henry, were more likely to have managed the

demise of the two princes.

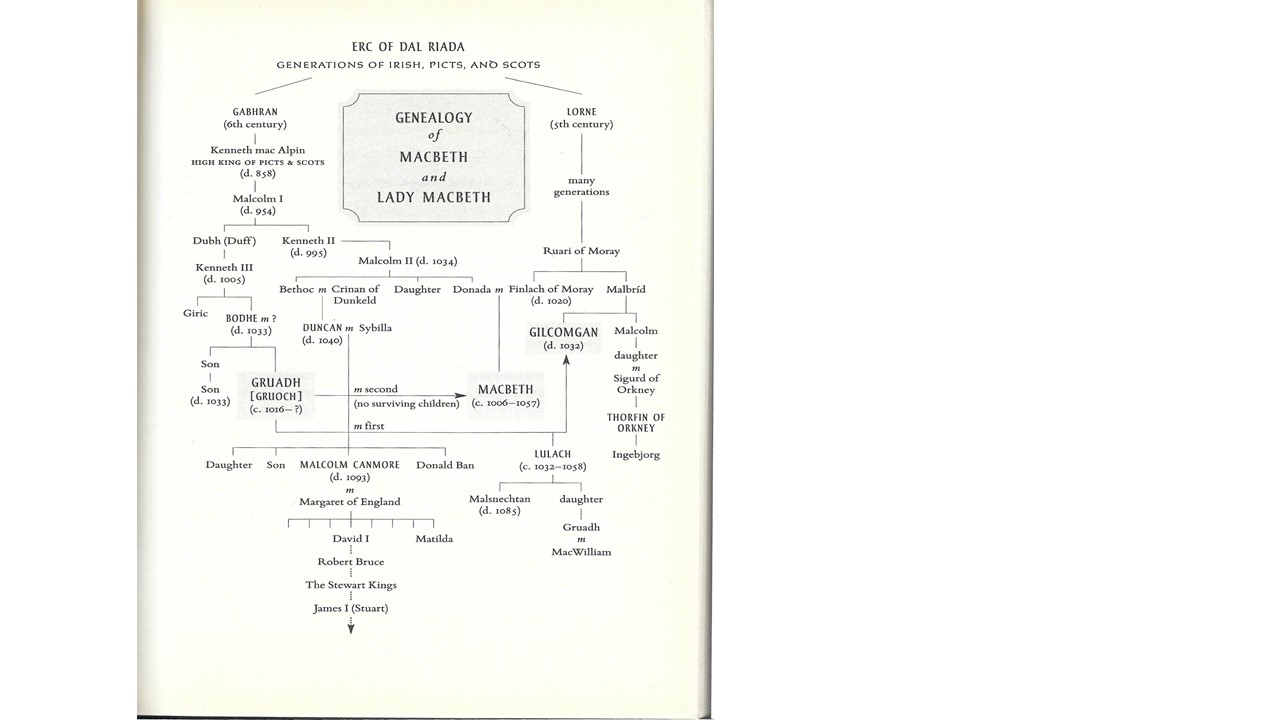

Forays

into genealogy not only provide historical details to help moor Shakespeare’s

plays, but provide us opportunities to see where he favored Drama over

historical Truth. In Macbeth, we have Lady Macbeth forcing Macbeth to

murder the good King Duncan in his sleep and then later committing suicide in

time for her husband to deliver his famous Sound and fury

soliloquy. Let’s take a look at the

genealogy of the actual Lady Macbeth, Gruoch, from Susan Fraser King's book, Lady Macbeth:

You

can see that Lady Macbeth, King Duncan, and Macbeth had a common ancestor:

Malcom I. Duncan and Macbeth were both

descended from Malcom II. In the history

books, Macbeth killed Duncan fairly on the battlefield. Duncan had been fleecing the Thanes so that

he could pursue his conquests to enlarge his kingdom. The thanes had to stop him. Nonetheless, Duncan is made out to be a

victim in Macbeth. But if Duncan’s

death is in 1040, that means that Macbeth reigned until his death in 1057, for

17 uncontested years. Lady Macbeth’s

dates, as women’s and slaves’ dates often are—not considered to be important—is

marked with a question mark. Lulach, Gruoch’s son by another marriage, became King

of Scotland for a year after Macbeth’s death.

And

here comes Shakespeare, choosing Drama over Truth, taking liberties with Lady

Macbeth’s dates. On some accounts, Lady

Macbeth actually survived Macbeth, which would put the lie to her suicide.

Works Cited:

Genealogies:

The Nevilles: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/359162139016484723/

The Beauforts: http://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/plantagenet_47.html

Edward the IV: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/74379831320531178/

Texts:

King, Susan Fraser. Lady Macbeth. New York:

Crown, 2008.

Shakespeare, William. The Complete Works of

Shakespeare. Ed. David Bevington. Boston: Pearson, 2008.

Tey, Josephine.

The Daughter of Time. New York: Scribner, 1951.

Because

I Can Teach:

Great lesson and teaching, Dr. Rich of charting Shakespeare's genealogies; it recalls how one family member explored the genealogies of my mother's ancestors in a fascinating way to navigate our family's history. The pedigree, called "a family tree," charted our lineage way before Ancestry.com. It too betrayed the basis of struggles and victories that defines the course of my mother's family history and how multiple family members came into existence and their successes.

ReplyDeleteAs Richard and Ann, who were cousins that played together and loved each other from childhood, I am also reminded, there once was a kissing cousin from my father's family who took quite the interest when we were teenagers. He certainly was attracted and attracted to me. However, as a young woman, I knew there was no way that we could more than cousins and resisted him. Finally, he got the hint and fled.

After that experience, regarding exciting pieces of history that you excellently charted about fiction and nonfictional, legitimate, and illegitimate ancestors. I have often understood why it is vitally important to be aware and know your family history for various reasons, such as family lineage and medical. If not, who knows, you could be kissing your cousin. But, then again, some like it like that.

Moreover, notably, as two accounts disagree on who Joseph's father was: Matthew says he was Jacob. In contrast, Luke says he was Heli, charting Shakespeare's genres, which has undoubtedly caused me to remember the most magnificent historical figure, the genealogy of Christ, the Messiah. Thus, all the generations from Abraham to David are fourteen generations, from David until the captivity in Babylon is fourteen generations, and from the captivity in Babylon, until Christ are fourteen generations. (Matthew 1:1-17, NKJV).

While the idea of using historical figures in stories, Shakespeare is far from the only individual who utilizes this idea as many authors before and after have done so. After all, when you use a historical figure, people already have expectations about the character's personality based on this history. This expectation has many benefits such as having to spend less time on characterization of a famous historical character because everyone already knows what they are supposedly like. Of course, one could use these expectations of a historical figure should act like to subvert them for the purposes of parody or historical fiction. This idea of using pre-baked expectation only works if people are familiar with the figure which includes history and even genealogy. After all, some historical figures' life stories came to be just because they were born into a royal house, as competition between families for titles caused members to do drastic things to secure their place. As such people are not looked at as just an individual but as part their family when discussing nobles. While understanding genealogy is important when using historical characters, it can be a bit disheartening to see how much of the legacy one leaves behind is connected to the family name rather than the individual. It just goes to show that people have a hard time looking at the merits and pitfalls of individuals as they often ascribe talents to a family rather than the person themselves.

ReplyDeleteMatthew Ponte

Your blog is very useful for me,Thanks for your sharing

ReplyDeletewordpress

blogspot

youtube

ហ្គេមស្លត់