It used to be flashlights under the covers with comic books—now

it’s phones, tablets, E-readers—there is something delicious about wanting to

read so much that we sneak it. I’m not

talking about social media, compulsive scrolling, online shopping, gaming, or

texting—that doesn’t count as reading—but being eager to return to a book does.

It would

seem that school should inspire the love of learning, as libraries do with

clubs and book fairs—but, unfortunately, school ruins reading for most of

us. In this blog post, I want to address

this problem and to offer a model to help us recapture our passion for reading,

so much so, that we abandon our Netflix, YouTube, and whatever new distractions

and addictions have emerged since I posted this essay—because we can’t wait to indulge

our love of books.

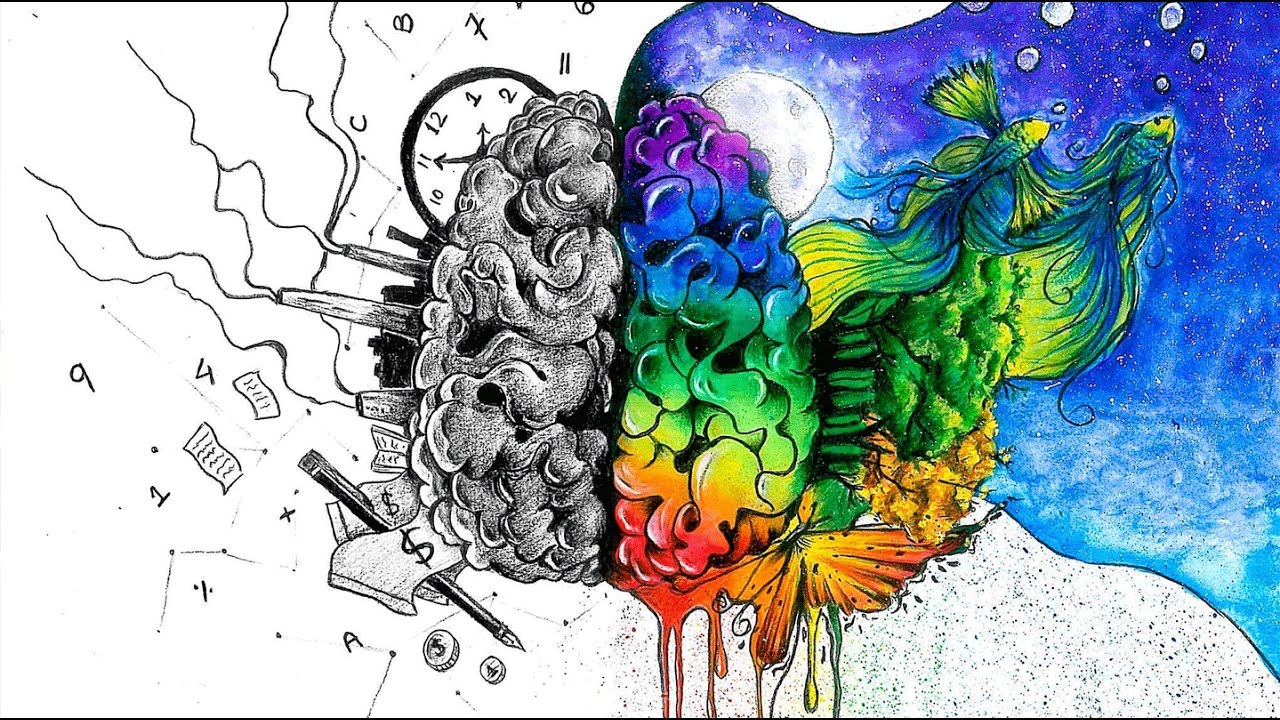

On one end

of the continuum is self-motivated, indulgent, glorious wanna reading—the kind we talk about with your friends and never

seem to see in a class; the kind where we fall in love with an author and

scramble to find everything she or he has written. On the other end of the

continuum is studying boring gotta textbooks

in anticipation of quizzes for get-it-over-with courses and grades.

But there are

some truly fascinating works presented in classes that belong on the love side

of the continuum—that are ruined by how they are “taught.” So, it’s not even so much what is included in classes as how we are harassed into, literally,

confronting them. It is truly tragic to

me that, when I ask my students in their senior capstone courses what they love

to read, they look at me like deer stunned by high beams in the middle of the

night. It has been so long that anyone

cared about their experience of reading—since they felt any passion for reading

themselves—that they don’t know how to answer.

Teachers placed themselves between them and books, co-opting, mediating,

and grade-quantifying their experience.

First, it’s such a ridiculous expression:

“I’m teaching Shakespeare.” Under one

interpretation of the expression, that’s ludicrous. Can’t teach Shakespeare anything—he’s totally

gone. And teaching conjures in all of us

the fear of metaphorically being the dunce shamed in a corner, having our

knuckles rapped with a ruler, or having to suffering detention. I reject the prevailing pedagogical model

that favors learning standard information over learning how to appreciate, that

favors assessment models over learning. Teaching should be about inspiring,

modeling for, and empowering students to create meaningful, and intellectually and

emotionally satisfying lives.

Reading was ruined for me,

too. That’s why I can write this. It has

taken me years to actually read through a book without taking notes, highlighting,

annotating the margins, and memorizing “key” ideas. It has taken me years to question whether a

book is worth reading through, just because it is a published work that someone

else required me to read. It has taken

me years to think of books as treasured friends to turn to for relaxation, adventure,

illumination. It’s only now that I’ve stopped, as a teacher, thinking of the

works I assign to classes as reading chores for myself.

To rehabilitate us all, I don’t

give quizzes to police whether students have read our texts. We develop an atmosphere of commitment and

engagement early on and most students come prepared—that is not negotiable. And

I certainly don’t give multiple choice tests.

Horrendously, there are some teachers who actually administer quizzes

and multiple-choice tests in Creative Writing courses. Really?!

I have discoursed on this in other posts, but my focus in our classes is

not what I want, but what students actually get from their readings.

I ask first, a show of hands, of

those who have read the portions of texts we will be considering that

meeting. Most students are honest, and

they know the rest of us will know—given the nature of our discussions—whether they

showed up that week. That’s usually

enough embarrassment for them to come prepared. After that, it’s all about making

the reading belong to THEM not to me as the arbiter of grades. And my hope is

that they will be able to recover from studying and learn how to enjoy the

readings.

One of the following questions will

often catapult us into our discussions: Did you like reading this? Why or why not? What caught your

attention? What did it mean to you? Is this good, engaging writing? Why or why not? What questions arose for you?

Just as a docent will show visitors

how to view new, experimental art in a museum, our class is a place where I can

model different doorways by which to enter a piece of writing, such as imagery,

theme, characterization, structure—but not everyone thinks alike, and not all

strategies will resonate with all students.

I don’t require all students to equally engage with all our

strategies.

Even more than discussion with the

whole class, my students discuss readings in small groups—that’s nothing

new. But I don’t micromanage the

direction these discussions will take with checklists of questions tending

toward “approved” responses. We come together after group readings to benefit

from the often unique and inspiring insights that emerge from the reading pods.

Here are strategies to remember if

we are to pull our readings away from the study end of the continuum back to

the love-of-reading end:

Less is more. Good books deserve rereading and

rereading. What’s my take away this time

from these pages?

Don’t be thorough—be deep. If I try to memorize and retain everything I

read in that limited corridor which is my left brain—I’ll drop it all. Best to

carry away one idea that matters, and to integrate it. Otherwise I’ll drop it all after the test and

it won’t be available to me after.

Take what you like, and leave

the rest. Most teachers would balk at this. My devotion is to inspire—not terrify.

Consider the continuum. Are you reading or are you studying? Ask yourself these questions as antidotes: Do

I love this reading? Why or why

not? How is this reading about me, and

not about the teacher or the test? How

can I use this reading to find deeper and more satisfying meaning in my life? How can I integrate this reading into what I

already know? What else could I read

along these lines that might be more inspiring?

I invite you, as well, to read the

blog post on TRUST—learn to trust yourself, as a reader, despite the

environment of distrust that standard education fosters. Will it be on the Test?: Trust and Joy in the Classroom. The love of reading and your passion for

literature will return if you make it your own.

I look forward to hearing about

your experience of how studying can ruin reading for you. How can and do you nourish

your love of reading?

Works Cited