A

question, by its very nature, invites or assumes responses. That is why questions are such powerful tools

for learning and developing ideas. By asking questions, we enhance the speed,

quality, and quantity of our learning. But

not all questions are alike: the better our questions, the better the answers.

Questions

are often triggered by the wh words: who, what when, where, why, and how.

Yes, and how. Originally, how was spelled and pronounced whow. Questions can also start with words such as do, can, are, is, were, if, and has, but, as you will soon see, questions

triggered by these words do not generate quite the same quality of responses as

the wh words do.

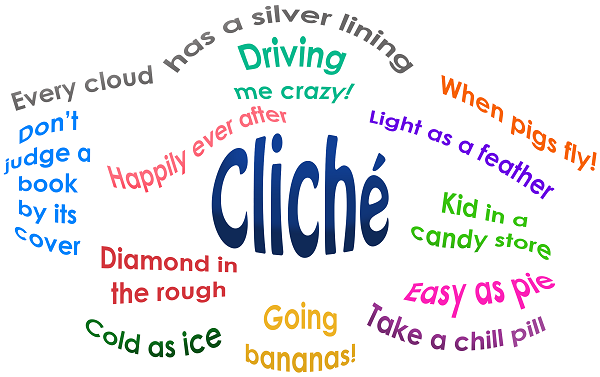

To

effectively ask and field questions, let’s distinguish several kinds:

(1) Good questions

(2)

Key questions

(3)

Unfair questions

(4)

Yes/No questions

(5) One-answer questions

(6)

Rhetorical questions

Good Questions

“Why

are our hearts on the left instead of the right side of our human bodies?” “Why do supermarkets place toothbrushes at

adult eye level and not alphabetize soup cans?”

“How do Christians argue for the existence of God?” “Why do some people

become alcoholics?” “How can we save the ozone layer?” “What might cure Alzheimer’s disease?” “What

happened to Uncle Frank so that no one in the family talks about him?” These are examples of good questions. Students of

language notice that good questions

tend to

ü Respond to an important human need

ü Are focused and specific

ü Promote thought

ü May question popular beliefs

ü Invite multiple, often conflicting answers

ü Lead to other questions

ü Suggest how they might be answered

ü Lead to good answers

ü Elicit an aha

response

ü May cause strong emotional responses

ü May meet with resistance

ü Can lead to collaborative work for answers

ü Make us respond with “That’s a good question!”

For example the question “How might we preserve

the ozone layer?” is a good question because it responds to an important human

need—to health of planet earth. The

question makes us think, has more than one answer, and leads to other questions

about the environment. The question has

led to good answers by people who have collaboratively pursued answers to the question. It isn’t a trick or unfair question. It leads people to say, That’s a good question. Whether in a classroom, lab, conference

room, assembly, or family table, good questions generate lively discussions and

promote inspiring challenges.

Key Questions

The

key question driving this post is “What the heck kind of question is that?” If we were to formulate key questions for the

Bible or the Koran, they might be “Who is God?” and “How can we best serve God?” Whether or not questions are explicitly posed

by an author, as readers, formulating key questions for the text will help us

to read more deeply. For the most

effective texts, the key questions are the good

questions. When the good question is not

explicitly posed, here are some ways to formulate them for what we read:

ü Posit a point of view of the author

ü Identify a purpose for why the author might be writing

ü Choose what seems to be an important purpose

ü Formulate this purpose as a wh question

As a writer, articulate your own sense

of why you are writing a particular piece. Ask

yourself these questions:

ü Why am I writing this?

ü What do I hope to discover in my writing process?

ü Who am I addressing as my ideal reader?

I find that whenever I am at a stopping

point in a particular piece of writing,

I turn my most recent sentence into a

question to relaunch my flow. So, for example,

I

will turn my previous sentence into a

question: “If I come to a stopping point

in a particular piece of writing, how might I relaunch my flow?”

Unfair Questions

“Are

you still beating your dog?” “What’s the difference between a duck?” “How come

someone says they saw you did it?” “You don’t want another piece of my pie, do

you?” “What is it like to be blown up by a bomb?” These and other such questions are unfair because

they

ü Assume something illegitimately

ü Are meant to trick responders

ü Often exact only one answer

ü May be unanswerable

ü Antagonize and confront

ü Lead or manipulate

For example, the question “Are you still

beating your dog?” is unfair because

it assumes that you beat your dog in the

first place. You can’t win. If you say “Yes,” then you are admit to beating

your dog. If you say, “No,” then you still

admit to having beaten your dog. The

question is confrontational and antagonistic.

In a

court of law, the opposing counsel would

object that it is a “leading question.” A fairer

approach would be to first ask, “Have

you ever beaten your dog?”

In an earlier blog, “Martha and

Mary,” I had originally asked an unfair question:

“How are your

teachers more Martha than Mary?” That

assumed that your teachers were more Martha and Mary. When a responder pointed out it was a leading

question, I revised it to “Are your teachers more Martha or Mary?”

Some

questions might be unfair because of the context in which they are asked.

For example, it could be unfair and embarrassing to

ask a person, “Is that a new hair dye?” at a formal dinner. But it can be entirely appropriate for a

hairdresser to ask this question of a client in the salon.

How

you phrase a question is crucial. The

question “What happened to

Uncle Frank?” may be a good question, whereas “What did

you do to Uncle Frank?”

is not. The question

“What’s the difference between a duck?” is nonsensical. But when comedian Grouch Marx asks it, the

question isn’t unfair—it’s funny.

Yes/No Questions

“Is

there an afterlife?” “Have you gone to the store?” “Are there moons around

Jupiter?” “Will there be enough ozone layer left at

the end of the twenty-first century?” “Should there be an extra microphone for

the event?” “Can you loan me some money?”

Such questions are yes/no questions because they invite just that—yes or no. They

ü Begin with some form of the words is, can, do, has, could/would/should,

or will

ü Do not

invite discussion or collaboration

ü Limit the range of acceptable responses

ü May be too general

ü Can be unfair, given the context

One-Answer Questions

“How

much is 2 + 2 in the decimal system?” “What was the cause of the Civil

in America?” “Who is the main character in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales?” “What

is the most important trait of a responsible thinker?”

“Would any sane person ever

want to kill an innocent child?” Or, my favorite question to avoid asking

students: “What is the main point of this text?” Such one-answer questions

ü Assume there is only one right answer

ü Occur most often in courses focused on information,

not thinking

ü Create a guessing-game atmosphere

ü Can be satisfying to answer “right,” embarrassing to

answer “wrong”

ü May create corrosive competition

ü May preclude questioning the question’s validity

For

example, the question “What as the

cause of the Civil War in America?” assumes, by the use of the word the, that there was one and only one cause of the war. Similarly, the question “What is the main point?” may shut down creative and critical thinking. If the questions were posed by a teacher in a class, it

could create a “guess what the teacher’s thinking” game. Some students would settle

for guessing, others might compete to be the first to say. Students who don’t want to play, might give

up, feel defeated, retreat into boredom, and sneak their phones.

Rhetorical Questions

“Would you

starve the children?” “How many people lost their lives to overdose?” “What

more could we have done to save them?”

Sometimes answers to such questions are meant to be so obvious—No, countless, nothing (respectively)—that

the questions are not meant to be answered.

They assume a particular answer and are used to affirm agreement.

If a question is not a request for an answer but a strategy

to persuade an audience of a predictable answer and point, it is called a rhetorical question (as the word rhetorical means “meant to persuade”). Rhetorical

questions

ü State, don’t ask

ü Are often used in rousing speeches and texts

ü Are meant to impress

ü Make a point without stating it

ü Imply one acceptable answer

ü Preclude an answer

ü Manipulate

Notice

that context—purpose and audience—determines whether a question is rhetorical. A villain might ask “Would you starve the

children?” as a request for an accomplice to do so. A writer seeking statistics to support an

argument for research on drug-use is not

merely posing a bemoaning rhetorical question when asking “How many have died

in this epidemic?” A Red Cross volunteer asking, “What more could we have done

to save them?” is posing a good question, not merely a rhetorical one.

Explore Questions

In

your classes, notice what kinds of questions are favored in class, and in assessment

instruments such as essays and tests.

Learn to discern what the heck kinds of questions your teachers are

asking and, if they are not asking good questions, how you might turn discussions

to asking them, yourself. Here are some

procedures you might take:

1.

Remind yourself:

The only dumb question is the one not asked.

2. Use the wh

words: Who, What, When, Where, Why,

(W)how

3.

Analyze select questions

by asking

a.

What the heck

kind of question is this? Good, key, unfair,

yes/no,

one-answer, rhetorical, undetermined?

b.

What kind of

response does this question anticipate?

c.

How could I

revise this question into a good question?

4.

Formulate key

questions for authors and in your own writing

5.

Practice

answering anticipated questions

6.

Ask questions throughout

your learning and writing process

7.

Repeat for

questions in other important areas of your life: family, relationships,

financial, spiritual, professional, et al.

Works Cited: